by Steven Lindner | Mar 1, 2016 | Industry Research and Recruiting Metrics |

In part I, Job Seeker Use of Job Searching Channels, we discussed the need to dig deeper and critically evaluate the specific story that is told by particular findings from different surveys seeking to understand the sources most frequently used by job seekers in their job search. We discussed how LinkedIn’s approach at getting at the “initial source” of hire was a meaningful step forward in this type of survey research. LinkedIn’s approach highlights the fact that different sources carry different relevance and importance to candidates, depending on the stage of their job seeking journey.

“Snackable” content is great when you are in a hurry but, like fast food, it’s also highly processed and probably not the greatest choice for nourishment. Putting it another way, we trust survey authors/sponsors to draw the right conclusions from a large amount of data and provide us with the 5-second headline about what does that mean in practice. More often than not, they are accurate in distilling that information. Sometimes, though, they may miss alternative explanations that may underpin the survey findings. Unless we take the time to closely examine the data upon which those inferences are based, we would never know.

Let’s take, for example, LinkedIn’s conclusion, based on their findings, that generational differences in the sources used by job seekers is a result of the degree of comfort each generation has with technology. Is a candidate’s comfort level with technology the only possible explanation for those findings?

A Question of Age or Stage?

We found LinkedIn’s survey1 particularly interesting because it not only reported “first awareness” job source for the overall sample, but also segmented the results by generation.

The sources that appear in the overall sample results make intuitive sense – we typically first learn about job opportunities by either searching the marketplace via job boards or job aggregators or by hearing about it from others, be it referrals, recruiters, or professional networks. Where things start to get interesting with LinkedIn’s results is when we look at generational differences in terms of how they first learn about the new job.

As one would expect, different generations reported initially becoming aware of their new (current) position via different sourcing channels. Below are the sourcing channels each of the three generations was more likely to cite, compared to the overall average:

- Millennials: Located it on third party website or online job boards

- Generation X: A third party recruiter / headhunter / staffing firm contacted them

- Baby Boomers: Heard about it from someone they knew at their new employer

LinkedIn’s report highlights those findings by drawing the conclusions that “Younger professionals are the most comfortable using online career channels.”

Let’s look for a moment at the results from another survey, conducted by CareerBuilder in 20154. This survey, among other things, investigated candidate behavior during the “orientation” phase of a job search (i.e., when a candidate first starts to look for a new opportunity). CareerBuilder’s survey shows that all generations tend to use similar tactics during the orientation phase. All generations search for jobs on major search engines, network with colleagues, family and friends, and visit job boards to assess the market.

Below we show CareerBuilder’s findings about candidates’ reported use of the online channels that correspond to the ones in LinkedIn’s survey:

| Generation |

Rate of Google Search Use |

Rate of Job Board use |

| Millennials |

72% |

51% |

| Generation X |

79% |

54% |

| Boomers |

69% |

46% |

Although Boomers report using online channels at a lower rate, their difference from the other two generations is not of a magnitude that would support a definitive argument that one generation is more comfortable with online career channels than another.

In light of this additional data, let’s pause for a second and ask ourselves the following questions:

- Are those findings really suggesting that the three generations have a different comfort level with online job seeking resources?

- Or is there something other than “comfort with online career channels” that may help explain the difference in how candidates from each of the three generations first hear about a new opportunity?

Based on our experience, we believe these findings have more to do with where candidates are in terms of their career stage and less with their comfort level with online job channels. Candidates who are in their 50s are clearly at a different stage in their career and life than candidates who are in their 20s, 30s, or 40s.

Based on Donald E. Super’s life-span career development theory, we can reasonably expect the three generations to be, on average, at different stages of their careers2; namely:

- Millennials: They are at a point in their lives where they are attempting to understand themselves, their vocational preferences, and find their place in the world of work (they are in what Super refers to as the Exploration phase). The older members of this generation have probably progressed to where choices are narrowed but not finalized, or are at the early phases of the next career stage, which Super refers to as the Establishment stage.

- Generation X: They are well into the Establishment stage of their career. Having gained an appropriate position in their chosen field of work, they strive to secure their position and advance to new levels of responsibility. The older members of this generation are moving toward and working on what Super refers to as Maintenance stage of their career.

- Boomers: They are working on the Maintenance stage, where the main career-related developmental tasks are comprised of holding on, keeping up, and innovating.

If we consider the different career development stages that each generation is expected to be traversing at the time, the sourcing channels through which they initially become aware of their new (current) position makes logical sense. The Millennials, being the most recent entrants in the workforce, still evaluating their options before committing to a chosen profession, and not having deep or wide established professional networks, cast the widest and quickest net to explore the available opportunities in the marketplace. As such, Google searches, job aggregators, and online job boards are perfect job sourcing channel for this group.

Baby Boomers, on the other hand, have been “around the block” of work, as the expression goes. They’ve established themselves in their chosen profession, know where they want (or don’t want to be) and have, by now, an expanded and strong social support network of family, friends, co-workers/ex-coworkers, bosses/ex-bosses, and professional colleagues and acquaintances that new opportunities quickly reach them (whether they solicit them or not).

Finally, for us, the result regarding Generation X, was the most intriguing. Those are individuals who have chosen a profession and have at least 7-10 years of related experience in their field. For them, it is a time for stabilizing, consolidating, building momentum, and moving up. At the same time, if they are relatively content with their current employer and how they expect their career to progress within the confines of that company, they are less likely to be actively looking to jump ship. When one considers the profile of the professionals who comprise the Generation X milieu and the searches that companies tend to farm out to third-party providers, the fact that Gen Xers are more likely to cite that a third party recruiter/headhunter/staffing firm was how they first learned about the new opportunity comes as no surprise.

So What? Practical Implications of the 2-Part Armchair Conversation

Surveys are a great way to gain insight into job seeker behavior. Each resultant statistic tells us a story about how candidates go after finding a new job. We then take that newly acquired (or updated) knowledge about job seeker behavior and we translate it into best talent acquisition, selection, and hiring practices. For example, corporate career sites matter – the stories told by multiple surveys in 2015 drive that moral home. Same with job postings on job boards or job aggregators. But are those channels equally effective for reaching all job seekers regardless of age or where they are in their career stage?

LinkedIn’s survey and the comparison of its findings with other similar surveys points to the fact that job seeker behavior is not that simple, linear, or unified. Understanding the complexity of the job seeker behavior and what job search channels, branding messages, etc. carry meaning and relevance for job seekers at different moments in their career and at different stages on their job search journey will only help us run more effective talent acquisition, selection, and hiring operations.

References

1 Why & How People Change Jobs. LinkedIn Talent Solutions, 2015

2 Super’s Theory. www.careers.govt.nz

by Steven Lindner | Nov 24, 2015 | Hiring and Retention, Talent Acquisition |

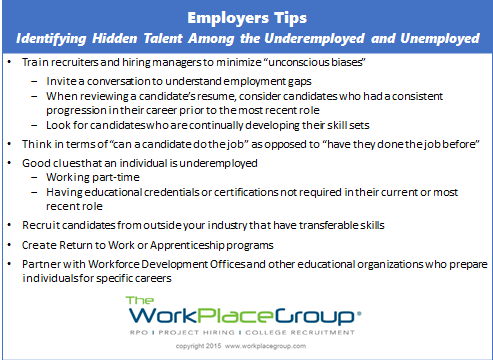

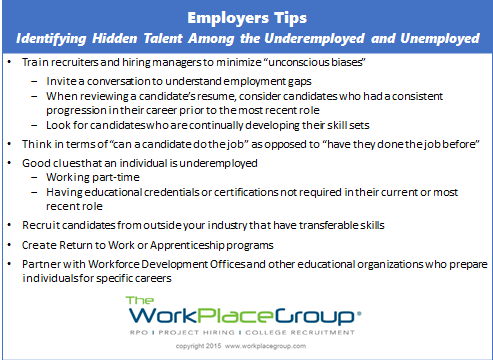

With the shift from an employer job market to a candidate job market, recruiters continue to be pushed to their limits in trying to attract and recruit new talent to their organizations. In this increasingly competitive job market, we will either have to rethink the way we recruit and screen candidates or accept the fact that our time-to-fill metrics will continue creeping up. Below we provide six tips for how recruiters, talent acquisition professionals, and employers can take an inclusive approach to identifying hidden talent among the underemployed and the unemployed.

Labor Market Update

Companies continue to add 250,000 new jobs a month, driving our national unemployment rate down to 5%. In Why Its Hard to Find Talent for Entry Level and Hourly Positions, we show how the unemployment rate is projected to fall to 4.5% by August 2016. This is great news for our economy, but New Labor Market Realities: Recruiting Friend or Foe? shows the impact the talent crunch is having on talent acquisition across industries. Our Talent Crunch Top 5 List summarizes the talent shortage that exists in our current job market.

Since June 2015, our national unemployment has been inching downward. Jobs continue to be added, particularly in professional and business services. In addition to the Top 5 Talent Crunch list, engineering services, health care services (especially in ambulatory health care and hospitals), retail trade, and food and beverage services also have some of the fastest growing number of job openings.

Yet the latest BLS statistics1 show very little downward movement in the number of workers employed part time for economic reasons, i.e., because they are unable to find a full time job or their hours have been cut back. This is also true for the marginally attached, that is, individuals who have given up actively looking for work. These two groups combined account for millions of potential job candidates.

Just think of the following ratios: At the peak of the recession, there were almost 7 job seekers per job opening. Today, that number has dropped to just 1.4 job seekers per job opening.

So what are recruiters and talent acquisition professionals supposed to do?

How to Not Miss Out On Potentially Good Talent

Without outsourcing jobs to other countries or importing talent from other countries, recruiters will need to broaden their talent acquisition strategies to address the impending talent shortage.

Recruiters and talent acquisition professionals will need to shift their organizations thinking — at least for some portion of their talent acquisition needs — from the jobs candidates have done to the jobs candidates can do. This shift in thinking means selecting candidates who want and can develop new skill sets. In other words, selecting candidates who lack the work experience but have successfully completed training programs or earned certificates and degrees from Workforce Development Offices and educational partners like Boot Camps, Trade Schools, and Colleges. Employers also may consider establishing their own Boot Camps, Apprenticeships, Return to Work programs, and training programs that help individuals re-enter the workforce or transition from other industries or positions.

When selecting candidates based on can do rather than have done, many things need to shift in terms of how recruiters and hiring managers assess candidates. Many tips and clues to look for on resumes and in social media profiles are included in Identifying Underemployed Workers.

Beyond talent acquisition and resume review, we need to change how we screen and evaluate candidates. The job interview process and the employment interview guide, in particular, needs to be re-examined. For example, job interview questions need to move from behavioral or experience-based questions to knowledge-based or situational questions. In order words, instead of asking what did you do when happened, you would ask what would you do or how would you do something?

When adding can do rather than have done candidates to your talent acquisition strategies, recruiters need to prepare and coach hiring managers to shift their thinking as well. Recruiters and talent acquisition professionals are well advised to educate internal corporate stakeholders on market realities and the talent crunch that now exists across multiple disciplines. Its also a good time to train hiring managers on unconscious hiring biases. After all, recruiters and talent acquisition professionals can find all the talent in the world, but we still need internal hiring managers to interview and make hire / no hire decisions.

For more insights on how to address talent acquisition needs please contact us.

1 The Employment Situation – October 2015. Bureau of Labor Statistics, November 6, 2015 (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf).

by Steven Lindner | Oct 27, 2015 | College Recruiting, Industry Research and Recruiting Metrics, Talent Acquisition |

Backwards is Forwards: Missing the True ROI of College Recruitment

Fall is upon us! And for those of us working on mid- and large-sized college recruitment programs, it’s the time of the year when all the thoughtful planning we’ve done over the summer goes into execution mode.

By this point, we have carefully selected our target schools and started lining up our onsite visits, career fairs, and interview days. We are armed with engaging collateral, intern and new grad success profiles, and job postings that speak to the soul of today’s college student. Our College Ambassadors are eager to get out and spread their contagious passion for our brand to future college hires. Our Hiring Managers and their teams are prepped for what’s to come. They have strategically planned and mapped out the meaningful and challenging projects that next year’s intern and new grad hires will be working on. Right?

We hope it is, because college recruitment is not a cheap proposition, at least not if it’s done right. According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE), the cost of an entry-level college hire in 2014 averaged $3,5821 (and that only includes the direct recruitment-related costs2; if one takes into account the time spent by hiring teams, that number becomes gaspingly larger).

A lot has been written about how to build and run a top-notch college recruitment program and for good reason – it’s a sizeable investment. According to NACE, the average employer with a structured college recruitment program converts 51.7% of its interns and 37.8% of its co-ops3. They extend job offers to 74% of the students they interview, of which 38.3% accept the offers4. Retention rates of new college grad hires were reported in 2011 as 92% and 69.2% after one- and five-years of employment, with larger companies having a harder time retaining new hires.

But are we measuring the right outcomes? When analyzing recruitment success, companies often overlook broader metrics that actually tie into business success. For instance, just like planning can help customers make smarter choices for long-term health, assessing the right hiring metrics ensures better employee retention and business productivity.

Based on our experience, as well as data from NACE, most companies with formal college recruitment programs do a good job on the operational piece the program. Where employers tend to miss the mark is with the explicit alignment of college recruitment outcomes to the ultimate business objectives. To accomplish such an alignment, data analytics specific to the longer-term business objectives are far more valuable in helping to shape college recruitment strategies and design internships and recent grad programs.

NACE suggests a number of common metrics5 to evaluate college recruitment programs, which include:

NACE, in its Standards document6, provides an evaluation of the various metrics in terms of their relative use and importance as reported by NACE employers.

- First, the metrics differ in terms of the data availability following the completion of an annual college recruitment cycle – i.e., some are proximal and some are distal to that end point.

- From the above listed metrics, Retention, Performance and Promotion clearly require the passage of one-to-five years post-recruiting a group of interns or new grads in order to have meaningful data to analyze.

- The second interesting observation, supporting our experiences in the field, is that distal metrics carry different degrees of importance and are used less frequently, overall, by employers.

However, aren’t those distal data points the ones that are the most meaningful to the business in terms of the bottom line? Aren’t those the most critical metrics that should be shaping and driving our college recruitment strategy?

Let’s look at two examples:

Example 1: Assume you work for a manufacturing company that recruits new MBA graduates for a leadership training program. There is a big push to recruit from Ivy League schools and regional operations-focused programs. After five years, your analysis shows Ivy League hires leave faster and perform lower than regional ones. The ROI favors local schools. Similar to how attract price-conscious customers, focusing hiring from high-retention campuses gives better value to your recruitment dollars.

Example 2: Your company pays $45K to attend Ivy League School X’s career fair but hires just one candidate. After three years, that hire files three patents—far outperforming peers. These insights reshape your view on the school’s ROI. Measuring such long-term impact transforms hiring decisions.

Conclusion: Staying focused on desired business results is what ultimately should drive your company’s college recruitment strategy. And in order to stay focused, we need to be measuring the right things (or putting the right measuring processes in place to capture what really matters to the business), even if our patience for data availability may be taxed. That is not to say that proximal process-related metrics such as Applicant-to-Hire, Interview-to-Hire, or Intern Conversion Rate do not matter—but without the ultimate goal in mind, we may have a very efficient and effective process that yields all the wrong results to the business.